A few years ago, I was hiking on a trail in Death Valley National Park, thinking about After Nature by Jedediah Purdy.

Purdy’s book is mostly historical. It traces four phases of America’s “environmental imagination”: Providential, Romantic, Utilitarian, and Ecological. During the Romantic period, we placed symbolic and aesthetic importance on unspoiled features like mountains and waterfalls—a way of thinking that helped create the National Park Service.

The fifth phase (our phase) might be called “Anthropocentric,” a term for how everything—from the climate to species extinction to the architecture of our omnipresent industry—has been touched by humankind. In Death Valley, I was thinking about Purdy’s thesis: that we need to adapt our imaginations, aesthetic preferences, and policies to this new reality. If we’re going to have an anthropocentric environmental imagination, we need to reimagine what’s beautiful, what needs to be learned, and what we ought to be visiting.

Our parks, since the beginning of the National Park Service, have been shaped by Romantic ideals. (Almost all celebrate mostly-undisturbed natural beauty.) As Purdy would argue, we ought not to discard these old values. But what sort of new parks should we be creating? Should we keep trying to buy up scenic land, or should we develop a new ecological imagination and visit new areas accordingly?

One idea is to designate parks around human destruction—like the chain of removed mountaintops in West Virginia and Kentucky. Scattered across the Appalachians, it covers roughly 1.5 million acres, which would make it among the biggest national parks in the Lower-48.

At Mountaintop Removal National Park (or “Broken Mountains NP”, visitors wouldn’t find pristine beauty, but human-made destruction, which would be beautiful in its own way. Maybe it’s not beautiful, exactly, but it evokes awe—or the “toxic sublime.”

Waterfalls and mountains do not have a monopoly on awe. The meticulously-planted Big Ag rows of hay can evoke awe. So can a dam, a refinery, a city, a pipeline. Personally, I was awed by the vastness of the Alberta Tar Sands and the Port Arthur refineries in Texas.

I don’t think feeling awe for these places is tacit approval; it’s acknowledgment of a rare amazingness, and of the fact that they can’t be wished away. In Mountaintop Removal National Park, we could learn about our destructive past, see the land slowly heal, and come to regard all aspects of nature—not just the pristine ones—as nature.

I was surprised to see so many visitors at Death Valley. (In 2018, it was the fifteenth most-visited park, with 1.6 million visitors.) That’s amazing for a place that gets two inches of rain a year, is deadly-hot for good portions of the year, and doesn’t fit our common ideas of natural beauty. How many people would drive through Death Valley if it was just a road through nameless BLM land? Not many.

Give it a cool name, call it a national park, and people will come. You could do the same with a lot of other places we typically wouldn’t seek out.

I have no idea if a Mountaintop Removal National Park, or a Tar Sands National Park, or a Love Canal National Monument is even remotely feasible. (Who owns that land? How much would it cost?) But it’s not a ridiculous idea. Every year, thousands of people visit Chernobyl.

People are drawn to the ugly and tragic, as long as it’s profound. Over a million tourists visit Auschwitz every year. Pompeii, Wounded Knee, Little Big Horn—places that move us, and in the case of Native American historic sites, probably do real good in educating folks about the struggles and injustices they’ve faced.

In Germany, there’s Landschaftspark, a park that includes the ruins of a twentieth-century ironworks, where they’re interpreting the industrial past and watching nature take over. Could we turn some abandoned Ohio rustbelt town into a park? Or what about the old grain elevators and silos of Buffalo, New York, which I’ve seen, and which are visually arresting? These places are darkly beautiful and they could tell a rarely told story about our industrial past.

Ideas for national parks for the Anthropocene

Silo City National Park – Buffalo, NY

Tar Sands National Park – Alberta, Canada

Pleistocene Park — Northern Alaska

The classic way a park is formed is this: The USA owns land and then, when the public realizes there’s something aesthetically or ecologically special about it, the government then converts it to a national park, or a fish and wildlife refuge.

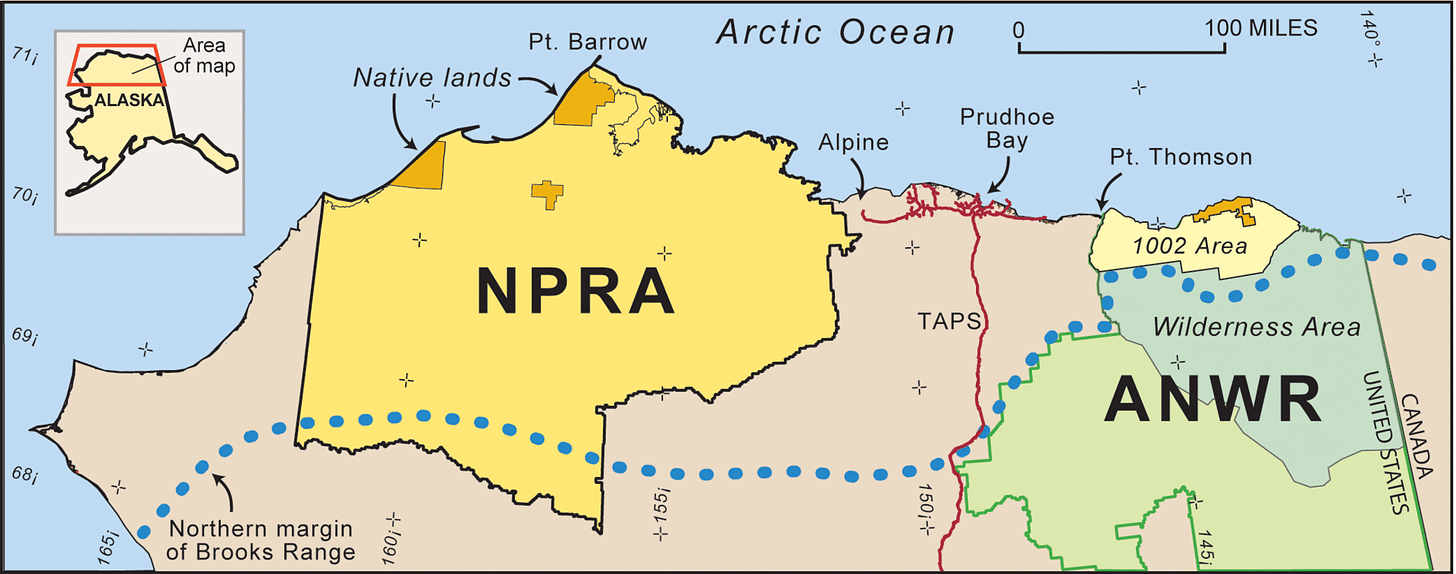

The problem is that there’s not many areas where the federal government owns a lot of unused land. That’s why it’s almost impossible to imagine a new “giant” national park. One exception may be the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPRA), which is 23 million acres—the size of Portugal or twice as big as the current biggest American national park (Wrangell-St. Elias).

When we’re done with all the oil extraction (and if consent is given from local communities), the NPRA might be a good testing ground for reintroducing de-extinctified animals that could possibly prosper in an ice-age-like environment. One could imagine animals such as the Wooly Mammoth, Steppe Bison, and Yukon Horse living next to present-day species like the caribou, wolf, grizzly, and musk ox.

Dust Bowl National Park – Great Plains

Love Canal National Monument – Niagara Falls, NY

Broken Mountains National Park – Appalachian Mts.

Soil Erosion National Park – Iowa

Passenger Pigeon National Park – Eastern U.S.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Out of the Wild with Ken Ilgunas to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.